This episode currently has no reviews.

Submit Review- Podcast |

- The Rialto Report

- Publisher |

- Ashley West

- Media Type |

- audio

- Publication Date |

- Nov 19, 2023

- Episode Duration |

- 00:35:44

Michael and Roberta Findlay's film's were more shocking that their peers. So who were they?

The post Flesh! The Untold Origin of the Findlays and the ‘Flesh Trilogy’, Part 1 – Roberta’s story appeared first on The Rialto Report.

Sex and violence have been part of movies since the very beginning.

Ever since Thomas Edison made and exhibited ‘The Kiss’ in 1896, an 18 second clip of a couple embracing, moviegoers have been shocked by onscreen depictions of lust. The outrage over ‘The Kiss’ was understandable: it was one of the first films ever shown commercially to the public, and kissing in public was prosecuted at the time. The Catholic Church knee-jerked instinctively, and said it was a “serious threat to morality and humanity”, and the film was met with the first demand for movie censorship.

Fast forward seventy years, and heaven knows what they would have made of Michael and Roberta Findlay.

The Findlays made a series of low budget films in the 1960s that combined sex with violence in a way that had rarely been seen. Sure, filmmakers like Russ Meyer or Herschel Gordon Lewis had already achieved success with exploitation flicks that mixed fornication with ferocity. But their visions gleefully and comically satirized the genre.

Michael and Roberta were different: theirs was a more shocking, sadistic vision that left an altogether different impression. More than with any of their peers, you find yourself looking beyond their work, instead wondering more about the filmmakers than the films. In short, you start to ask, “What kind of people made these movies?”

Over the last few years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to friends, family members, collaborators… in fact, anyone who knew Michael and Roberta back in the 1960s – including Roberta herself – to dig deeper into who the Findlays really were and where they came from. The new information I found was surprising, unnerving, and sometimes disturbing – and it changed the way I view the films themselves.

This is Part 1 of ‘Flesh: The Untold Origin of the Findlays and the ‘Flesh Trilogy’’ – Roberta’s story.

This podcast is 36 minutes long.

———————————————————————————————-

Roberta Findlay walks into a midtown Manhattan bar.

Unruly dark mop, giant black sunglasses, scowling bad attitude. She looks like Bob Dylan in ‘Don’t Look Back.’ Or a microwaved Anna Wintour.

“I don’t like people,” is her opening gambit. “Especially not those who watch my sex movies. These people are creepy. With deep psychological problems.”

I’m lucky, I guess. I’ve known Roberta for years, and she insists I am one of her two favorite living people. I’m flattered until I learn that Dick Cheney is the other: “I like arrogant men who mistreat me” is her explanation.

Dick Cheney mistreated you? I ask.

“I can dream,” she grunts.

Today Roberta has decided to cement our friendship. She gifts me the copy of ‘Hollywood Babylon’ that sat at the bedside of her long-deceased husband, Michael. I’m strangely moved. This 1959 collection of crime-soaked, sleaze-boiled gossip from Hollywood’s golden age underbelly had been an inspiration to him when he first became a filmmaker in the 1960s. Their film titles bore the evidence: Satan’s Bed (1965), Take Me Naked (1966), The Ultimate Degenerate (1969), and the infamous Flesh trilogy (The Touch of Her Flesh (1967), The Curse of Her Flesh (1968), The Kiss of Her Flesh (1968)). Tormented black-and-white nightmares trading in imaginative, misogynistic violence. Kenneth Anger’s aesthetic updated to a low-rent 1960s New York tenement world.

Their movies found an audience, then as now. For a time, Michael and Roberta reigned supreme in grindhouse theaters as kingpin auteurs of low-budget east coast sex and violence. Their fingerprints were evident in every frame: they produced, directed, wrote, and acted in all their films. Michael even starred – as one-eyed, paraplegic serial killer, Richard Jennings, in the ‘Flesh’ movies.

Except that Roberta now disputes her involvement in these early operas of sadism. I point out that her name, or pseudonym, appears in all the credits. Furthermore, crew lackeys remember her shooting the films, and cast members recall her active involvement. Roberta waves away my persistence.

“I was adrift in that maelstrom. I was underage. I didn’t know what I was doing. I never knew what I was doing. I have no recollection of any involvement. Just leave me alone. I was young. Too young. Underage, in fact. You hear me? Underage.”

Not that Roberta is prudish. She admits to making a string of later hardcore sex films – without Michael – though she is quick to dismiss them: “I deplore anything violent, but sex… I didn’t care. I made the movies for money, and because I liked to shoot as a cameraman. That’s what I liked doing best: being behind the camera, shooting and lighting. That’s where I was happiest in life. I still miss it today.”

But I return to the question at the heart of their 1960s movies. The conundrum of her cinematic union with Michael. What kind of couple would make films that so single-mindedly focused on a such a twisted disturbance of revenge, murder, and sex? Was it merely a cynical commercial tactic? Or did it come from a deeper chamber of the soul?

Roberta is unimpressed by the query. Open-book self-analysis is anathema to her. Questions that probe motivation irritate. Her silent response smacks of annoyance, then defiance. I ask again. And finally, without warning, she opens up.

“What can I tell you? Michael was a troubled and deranged man. A cracked, overgrown man-boy. And I was damaged goods. Product of an isolated, difficult childhood. For a time, we only had one another. So we clung to each other. There was no calm, sensible person in our relationship, and therefore all our problems were amplified: all our scars, fears, obsessions, phobias, and neuroses. And we had a lot of them. We weren’t normal people.”

Let’s talk some more about that, I suggest.

*

When were you born? I start.

“That’s an indiscrete and ungentlemanly question,” comes the reply.

I apologize. How old were you in 1962 then?

“That’s the same question – with a tricky calculation. I can’t do math. And I can never remember my age.”

All the interviews with you, going back to the early 1970s, say you were born in 1948. On December 30th. But I’m not sure that’s correct.

“December 30th? Yes, that’s right.”

But what year?

“Oh, I don’t know. I’ve forgotten over time. Why is this important anyway?”

Because you said that you were underage when Michael and you made your first films. So I want to figure out the timeline.

“Let’s say I was born in 1948 then. And move on.”

Here’s the problem I have with that. I have production records from the first film that you appeared in. Body of a Female. That film was shot in the summer of 1962. You had several nude scenes in it. But that would mean you were only thirteen or fourteen at the time of the shoot.

“I don’t know anything about that. I was underage when the ‘Flesh’ movies were made. That’s all I know. That’s why I know nothing about them. I was underage. Now leave me alone.”

*

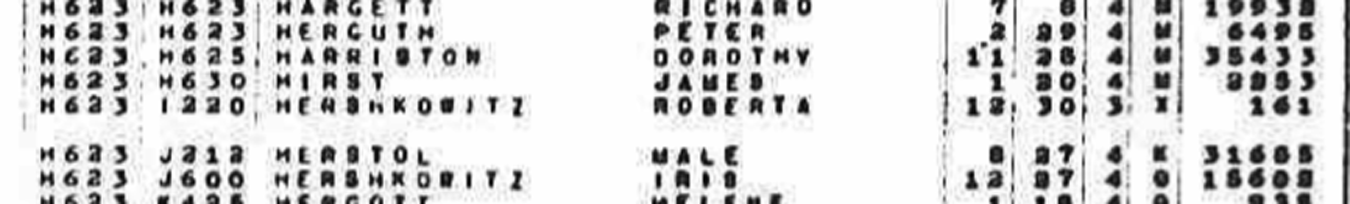

Rubeena Hershkowitz (no middle name was necessary as it was already a mouthful, she says) would have been known to her goy friends as Roberta, except that she had no friends. More on that later.

She was born in the Bronx to Hungarian Jewish parents. In an undetermined year.

Moses Aaron Hershkowitz was her father, and a mean villain. “An evil man. He didn’t like anybody,” Roberta says. “And in return, nobody liked him.” What Moses lacked in charm and warmth, he also lacked in humility and generosity. Born into a family in rural Hungary with nine brothers and sisters, he stood out from the wolf pack by his street-smart intelligence and angry belligerence, a combination that did him little good. At Yeshiva, the rabbis beat him regularly for his back-chat and bad attitude.

“He was obstreperous and rebellious,” says Roberta, “as well as a violent agoraphobic who suffered panic attacks in crowds. I saw his first passport photo once: he was very good-looking as a young man, devilishly handsome, with a large mustache. But boy, he was bad.”

Moses dealt with his frustrations by becoming a small-town bruiser, part-time rat-catcher, and quick-fire brawler. When he was twelve, he ran away from home. Roberta remembers family lore about his vanishing act: “Apparently, he did some stuff and had to flee. I don’t know what it was. I have no idea. But that’s the story.” Moses returned home several years later at seventeen, only to be greeted by his mother’s withering contempt: “Oh, look, he’s back. And this time, he’s brought a little suitcase.”

He was also cursed with a spectacular lack of respect for authority. When conscripted into the Hungarian army, Moses shot himself in the foot, literally, to avoid serving. Instead, he shacked up with a local woman, Matilda, and they had two sons, Maximilian and Alexander. But familial responsibilities failed to hold his interest, and at 19, with a feral reputation and one functional foot, he limped away. In the late 1910s, he slipped into neighboring Romania, somehow acquired a passport, and headed north until he reached the German port of Hamburg. There he boarded an ocean liner, The Leviathan, which set sail for New York. He never saw his parents again, disappeared or liquidated by the Nazis in the years that followed.

*

“This isn’t working,” Roberta flatlines.

What do you mean? I reply.

“It’s boring hearing about anyone else’s life. And hearing about their childhood is the worst. When I read a biography, I skip the first 100 pages every time. I’m just not interested.”

I disagree. I’ve read several recent articles about your life. Film magazines, liner essays for film releases. Nearly all are terrible.

“In what way?”

In the most unforgivable way: they’re boring. And your life story deserves better.

“You’re weird.”

Do you want to add anything to that?

“You’re a voyeur. You have a strange interest in things no one else is interested in. I think that you’ve led a perverted life, and your childhood would provide some context for the arrogant person you’ve become.”

Maybe. But I didn’t make films in which strippers are killed by a rose with thorns dipped in poison, by a toxic dart shot into the stomach, or by daggers, buzzsaws, and crossbows. You’re the interesting one.

“I told you I don’t know anything about those movies. I was underage.”

That reminds me: you still haven’t told me how old you are.

*

Newly arrived in New York, Moses, now Americanized to ‘Morris’, kick-started a new life living in a three-to-a-room, crowded tenement on the Lower East Side, where he continued his mercurial, rowdy ways. He took work as a ratcatcher again, but within months of his arrival, was arrested for grand larceny, and after the first three years had assembled a rap sheet as long as a midtown skyscraper.

Roberta describes him in begrudging Tommy-gun prose: “An outsider. A wild man. A Communist. And dangerous. He was as hard as nails and tough as leather. Always a fighter, forever beating people up. If he’d had a gun, he’d have been a serial killer.”

Morris didn’t always find trouble: sometimes it found him. Roberta remembers one time when he was attacked on the street. Morris always went to work at dawn when the subway was empty because of his acute agoraphobia. He was attacked by two muggers. He self-defended, retaliated, and beat the aggressors to a pulp, leaving their unconscious, bloody bodies at the side of the street. He called the cops to report the mugging, but he’d inflicted so much damage on them that the police tried to arrest him instead.

Morris spoke Yiddish, Hungarian, and Romanian, but no English. Somewhere along the line, he ran into a first cousin named Rachel who went by Lillian/Lily. Lily was several years his junior. She’d been born in the same region of Hungary as Morris, but brought over to New York as a baby by her seven brothers and sisters. And, unlike Morris, she spoke English fluently. Morris saw an opportunity: he proposed marriage to her so she could teach him the language. “Good deal for him, I guess” says Roberta with a shrug.

The couple had three children: Janice and Ira in quick succession, followed years later by an afterthought, Roberta: “I was born when my mother was in her forties,” Roberta says, “which was not recommended at the time. Plus my parents were immediate cousins. All very unhealthy. I could’ve been a cretin, an idiot! Maybe I was.”

From an early age, Roberta was horrified by her father and his ways: “He filled me with fear and terror. He used to beat me up regularly starting from when I was very small. And my brother Ira as well. I remember him breaking a chair across my brother’s back, almost splitting him in two. I was scared witless by his hands. Huge hands. He seemed to me to be the strongest man in the world. He had a quick temper and could break anything just by hitting it. The beatings would continue for years.”

Morris’ violent impulses weren’t restricted to his New York family either. When Roberta was six years old, the family were present at a bar mitzvah attended by relatives, and Morris was confronted by the partner he had left behind in Hungary, Matilda, who’d turned up with their two sons, Maximilian and Alexander. Unbeknownst to Morris, they’d all emigrated to the United States and were now living in a studio apartment down by the docks on Maiden Lane.

Roberta remembers: “His sons were grown men by then, and they looked exactly like him. They approached my father and challenged him, saying he’d abandoned all of them in Hungary. They wanted answers. My father just laid them out and continued with the festivities.”

Was Morris ever formally divorced from Matilda?

“I have no idea. I don’t know whether he was married in Hungary and then divorced. Or if he was married to them both at the same time. I don’t even know if he was legally married to my mother. We still don’t know who was married to whom. Like I said, he was a bad man.”

*

So when you were born, I ask again?

“My sister was the oldest, 1930, I think. My brother came next, around 1938. And I’m not going to tell you my year.”

Is that because you can’t remember, or because you don’t want to tell me?

“I thought you said this would be fun? Who’s going to read this? Why does it matter?”

It’s important because we’re trying to set the record straight. Because the year normally quoted doesn’t seem accurate. And because I’m trying to work out how old you were when you met Michael, and how old you were when you made films in the 1960s.

“Let’s say I can’t remember. Or better still, let’s say 1948.”

Let’s say you let me call your brother so I can ask him?”

“No. You’re not going to speak to Ira about this.”

Ok, so what about slipping me some ID with your birthdate on?

“You’re a pervert. Stop torturing me.”

*

The Hershkowitzs lived at 2104 Vyse Avenue, a 26-unit apartment building in a southeast neighborhood of the Bronx called West Farms Square, near 180th St, a popular shopping area. It was also next to the Bronx Zoo: “we could hear the lions roar at night,” remembers Roberta.

It was a six-floor walk-up, and the Hershkowitz family had an apartment on the fourth floor: “It was definitely not a tenement. It was a step-up from that, and it was on a corner and that was considered high class. You’d made it if you had a corner place.”

Roberta was raised in a Jewish cocoon: an exclusively Jewish neighborhood in a home in which her parents spoke Yiddish to each other: “My parents were essentially Jewish peasants. Truly from a shtetl in Hungary. I never met a non-Jew until I was in junior high school. There were a few black kids, but they were children of the janitors of the buildings we lived in. Apart from them, it was all Jews.”

Not that being religiously Jewish was a feature for Roberta: “My mother tried to be a good Jew, but she had no concept of what any of it meant. She thought it had something to do with cooking: on Rosh Hashanah, you bake rugelach, and at Passover, you change the dishes and eat matzo instead of bread. She didn’t have a clue.

“As for me, I never had any interest in religion. I’ve never even been to temple. My mother used to go to synagogue once a year on Yom Kippur but she didn’t know why she was there. My father would take me along so we could stand outside and he could ridicule the whole affair. That made him laugh. He thought the whole thing was ridiculous.”

By then Morris had become a dry cleaner by trade. For years, he made a daily ninety-minute commute to Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, reading The Daily Worker, the firebrand newspaper for the communist party to which he belonged. And his troubles with the law continued. One time he was arrested for not paying his debts. Or rather for half-killing an unpaid debtor who complained.

If her father was colorful, his wife Lily lived her life in black and white: “My mother was a gray individual. A non-entity. She didn’t do or say much. A regular, normal-grade anonymity. Not attractive either. She just wasn’t pretty.

“They said she was good at numbers, whatever that meant, so she found work as a bookkeeper. She had her columns and such, and worked for Maidenform, the retail chain selling underwear and pajamas. I was close to neither of my parents, and they rarely talked to me.”

With siblings much older than her, Roberta felt like an only child. Ignored by her working parents, she was actively resented by her sister who was forced into the caretaker role for the infant: “Janice didn’t like me. She said I’d gotten all the privileges that she hadn’t had because she was born during the depression.”

Like what, I asked? “Like lamb chops. She said that made me the chosen one, the lucky child. I didn’t see it that way. For a start, I didn’t eat so I didn’t care about lamb chops. My mother had to force me to eat. I was never hungry. I weighed nothing. I just drank.”

Ah yes, alcohol. Roberta and I have been meeting up for years, and every evening follows a similar pattern: in short: I eat, and Roberta drinks. Double Jack Daniels on the rocks. Several of them. Her comments start before the first drink ends.

“Eating is cheating.” “Call yourself a man?” “You are nothing but a lily-livered limey.” “When are you going to have a proper drink?”

If this is how Roberta treats one of her favorite living people, I’m grateful not to be on her shitlist.

I ask her if she remembers her first ever drink. “Yes. My father started giving me gin when I was eight years old. He was a drunk – which at that time was unusual for a Jew.”

You’ve continued since then? “Oh yes. I liked it from the start. And I introduced alcohol to the men in my life too. Like Michael. And later Allan Shackleton. And the rest. They all took to drinking in a big way after me.”

I’m sure they did, I whisper.

And when did you start smoking? “When I was twelve. Somebody took me to the roof of my building. I don’t remember who it was. And said, “Here, you want to smoke?” I said, “Okay.””

Wasn’t that a young age to start in those days? “Of course it was. In fact, I got lung cancer a few years ago. I always assure my doctor that I don’t smoke. But I still do.”

I tried to picture a young Roberta. What happy childhood memories did she have? “I can’t think of any. I read a lot. I read before I started kindergarten. Everything came from the library. There were only three bought books in the house. I was in my own frightened world, hungry for knowledge, and keen to escape by getting my hands on books.

Give me an example of a book that left an impression: “I read ‘The Well of Loneliness’ when I was eight. It was one of the three books my parents had. God knows why. It was about lesbianism. It was written in the 1920s and a British court judged it obscene and banned it because it defended “unnatural practices between women.” I read it under the covers at night with a flashlight. I didn’t understand how or why two women would want to be together like that. I didn’t understand it then. I still don’t understand it now.”

But what did a drinking, smoking, pre-pubescent girl do for kicks with her friends, I wondered? “Oh, I had no friends. None. I suffered from agoraphobia just like my father so I was full of anxiety that shut me down. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to make friends. I just didn’t know how to do it. So I didn’t have any friends. I had a girlfriend in junior high school for a week. But that was it. I had no other friends at all. Zero. Zip.

What about boys? “No. I wasn’t interested in any of them. And the girls? I detested them.”

So sex didn’t become a factor? “No. I had no interest.”

*

When she was five, Roberta discovered an all-encompassing activity: playing the piano. A beat-up Sohmer was winched through the Vyse Avenue fourth-floor window, and Roberta was made to start a rigorous schedule of lessons with a ninety-year-old disciplinarian tutor. At first it was a foreign world: no classical music had ever been played in the family apartment. Her only exposure to music had been a small selection of 78s by popular singers like Bing Crosby.

But she was a fast learner. She quickly dispensed with the inane, nursery rhyme tunes put in front of her and moved onto the serious composers. Mozart, Schubert, Rachmaninov. Especially Rachmaninov. For the first time in her life, her parents took notice of her, amazed at her talent: perhaps they had a gifted, talented prodigy in the family, what a mitzvah. With the right teaching, maybe she could achieve fame and, more importantly, fortune. Morris had high hopes: “She was an accident, but perhaps not a mistake,” he said hopefully, even though he barely spoke to her for twenty years.

They bought records to encourage her, and then ordered her to practice more. So she did: “I practiced every day. Hours and hours of practice. I still wasn’t aware of classical music. I just had music put in front of me, so I played whatever it was. I was disciplined and I seemed to do nothing else.”

For Roberta, the activity was as successful as it was joyless: “I was an excellent sight reader and I advanced through the repertoire quickly. I got better and better. But I didn’t realize that you were supposed to enjoy it. It was a chore. I just did what I was told. I played the piano into the night, and never thought of it any other way.”

*

Were you in therapy at all as a child, I ask?

“No. Why? Do you think I’m nuts?” A question answering a question.

You went through a lot in your first ten to fifteen years: a physically violent father, an emotionally absent mother, siblings that were distant, cold, and resentful, debilitating panic attacks caused by agoraphobia, high pressure expectations to become a successful pianist which caused you to practice obsessively for hours each day which you didn’t enjoy, no friends, and you started drinking and smoking from an early age… that’s a heavy burden.

“Well, I did see a therapist when I was a teen. But not in the way that you mean.”

Roberta looks out of the window.

Can you tell me about it, I ask?

*

“I was in high school, thirteen years old. The head of the music department decided I should eventually go to City College like he had. As preparation, he got me to participate in a group called The Friends of Music. It was a nationwide organization, and their purpose was to hold musicals every month. Everyone in the group was musical in one way or another, except for one man who couldn’t play anything. He was just a devotee. His name was B.

“B was in his mid-30s, and he was a child psychologist. He was studying for a PhD. He lived in the Bronx. West. Everybody seemed to live west. Not too far from where I was. He told me later that he joined the group because he was looking for young Jewish girls.

“B wasn’t such a good-looking chap. Totally bald with glasses. Big guy, it seemed to me, but I was even smaller back then. Tiny. He just seemed gigantic. He was married, or rather he had been, but he didn’t talk much to me about his wife.

“He invited me out. We had a brief encounter that day. His bedroom was adorned with blue lights, and he played the Rachmaninoff Second Piano Concerto. I’m a sucker for that. I’ll lie down for anybody who likes Rachmaninoff.

“That was my first sexual experience. I didn’t know how it worked. It was rape technically.

“After that, I had a relationship with him that lasted for two years. Until I was fifteen. Usually in his apartment. He would put on the Rachmaninoff record, and then it would happen. Over a period of many months.

“For two years he was like a boyfriend. He took me out sometimes. He had a car. Music recitals. Museums. Restaurants, like a hamburger joint on Fordham Road in the Bronx. I’d never been to a place like that because my parents never ate out. Once he took me to Jones Beach. I remember I played in the sand while he sat in a chair and watched me. And during this time, he also asked me to take tests for his psychology papers.

“But mostly it was about sex. I was never interested or curious about sex. Or even excited about it. I liked it at times, but I just did what I was told. It wasn’t important to me. I guess I knew the whole thing wasn’t right.

“And he took pictures of all our encounters too – I think they were Polaroids. He showed me the pictures. I have no idea what happened to them after that.

“He once asked me to screw his friend. I didn’t do that… but only because I didn’t show up. I never said no to anyone. I didn’t think I had the right to. I would’ve done whatever he wanted me to.

“B never came to my apartment. But eventually, my parents got news of what was happening. I never found out how they discovered. They tried to confront him. They went to his place and started banging on his door. I was inside, scared to death. They shouted, “We know you’re in there.” but he never opened the door. They did that a couple of times. And when I returned home each time, we never talked about it.

“And then one day, when I was fifteen, he decided I was too old for him. We sat in his Hillman Minx car, and he said, “We have to stop seeing each other.” I cried and cried and cried and cried. I was devastated. I didn’t know else to do.

“I never saw him again after that night.

“Many years later, decades had passed, I was seeing another therapist because of my panic attacks. He told me he knew B, and that B lived close by. Apparently, B had since come out as gay and was now dying of AIDS. That was the last I heard of him.”

*

Roberta’s social dislocation wasn’t helped by an overly-accelerated path through school. In the fourth grade the school authorities decided that her reading level was that of a sixth grader – so they recommended skipping fifth grade. Then in junior high school, her academic aptitude led to a special program called Rapid Advancement – which meant she skipped the eighth grade, going straight from seventh to ninth. Being born on December 30th, she was already the youngest in her year. Long story short: Roberta graduated high school when she was barely fifteen.

Equally swift was her ascent to becoming a concert pianist. She was twelve when she performed her first solo concert – at Carnegie Recital Hall in a competition for the American Music Teacher’s Guild. Other contests followed, including a recital at Town Hall, and then at sixteen, a breakout concert with the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra.

From a distance, it seems like parts of Roberta’s life lurched fast-forward into adulthood long before she stopped being a young girl.

*

Roberta and I meet again. This time I’ve made a break-through. I tell her that I dug through official New York birth records and finally found a record of her birth.

Roberta Hershkowitz. Born in the Bronx. December 30th.

1943.

That’s five years older than the widely quoted birth year of 1948. It means she met Michael, in 1959, aged 16, just after she graduated high school. She was 19 when she appeared in ‘Body of a Female.’ And 23 when she and Michael started making the ‘Flesh’ trilogy. A naïve, damaged, young woman, rather than the underage girl she claims. But now, confronted with the truth of her age, I wonder if that distinction is arbitrary, irrelevant.

Was it mere vanity that has made Roberta hide her real age? Or does she claim to be younger because, in some way, it would absolve her from involvement in the controversial, violent films that she dislikes so much, like the ‘Flesh’ trilogy? Either way, it seems a detail now, and I feel guilty for having pressed her.

Roberta is unimpressed with the news: “That can’t be right,” she insists. “No, no, no. That just won’t do. I don’t know where you get that idea. And I don’t agree.”

I change subject and ask her if her success as a teenage pianist made playing the piano more enjoyable for her: “No.”

Was there at least a piece that you liked playing? “Yeah. There’s a Mozart piano concerto. Number 20 in D-minor. It’s his darkest, most cruel piece. That seems appropriate. And I like that.”

We’re quiet for a while.

Roberta breaks the silence: “I haven’t played the piano in years,” she adds with a shrug.

I say I’d like to hear that Mozart concerto.

That evening, in her apartment, she plays it. And the dark, cruel music of Roberta Hershkowitz’ piano fills the New York night sky one more time.

*

The post Flesh! The Untold Origin of the Findlays and the ‘Flesh Trilogy’, Part 1 – Roberta’s story appeared first on The Rialto Report.

This episode currently has no reviews.

Submit ReviewThis episode could use a review! Have anything to say about it? Share your thoughts using the button below.

Submit Review