- Publisher |

- SoundVision Productions

- Media Type |

- audio

- Podknife tags |

- Humanity,

- Natural Sciences,

- Science & Medicine,

- Society & Culture

- Categories Via RSS |

- Natural Sciences,

- Science & Medicine,

- Society & Culture

This podcast currently has no reviews.

Submit ReviewWhat if you had an idea that you believed could change the world? What if that idea was a tornado machine? In this episode we ask, what drives some people to pursue an idea for their entire lives?

Man-TRBQ-18.mp3">http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Tornado-Man-TRBQ-18.mp3

Man-TRBQ-18.mp3">Download audio

Retired engineer Louis Michaud believes he has an idea that could solve the world’s energy problems. He calls it an”Atmospheric Vortex Engine. ” For 50 years, Michaud has been working on a device that he hopes someday will generate mile-high tornadoes from warm air heated by the sun or waste heat from power plants. The updraft would turn turbines and produce power. Lots of power, he believes. All he has to do is prove it.

This story first appeared on The Adaptors, a new podcast hosted by TRBQ producer Flora Lichtman.

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

A very brief announcement. Really, really brief.

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/TRBQ_Shorts_Shortly.mp3

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

You can vote when you’re 18 and drink when you’re 21. But when do you really become an adult?

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/TRBQ_Podcast17_Adulthood.mp3

Psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett says people in their 20s are in a different life-stage than people in their 30s. He coined the term “emerging adulthood” to describe the years between adolescence and full adulthood. Producer Flora Lichtman met up with him to hear more.

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

(Music)

OLSHER: I’m Dean Olsher. And this is the The Really Big Questions, the podcast that asks — you guessed it — big questions. Like what it means to be an adult. Research shows that how we define adulthood has changed in recent years. Psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett says that historically, almost all cultures defined adulthood through marriage. Today, not so much. In a national survey asking which of 40 criteria are most important for adulthood, Arnett finds a different answer.

ARNETT: Marriage consistently ends up near rock bottom.

OLSHER: How are we redefining adulthood? TRBQ producer Flora Lichtman investigates.

LICHTMAN: I’m out pounding the pavement to see if my neighbors can help us think through our big question du jour. What does it mean to be an adult?

PERSON 1: That’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about actually. For me, it’s have I developed myself enough as a person.

PERSON 2: I don’t really know yet, because I’m not an adult myself.

LICHTMAN: How old are you?

PERSON 2: I’m 18.

PERSON 3: I’m not an adult yet. I still think I’m a kid. I’m 65!

PERSON 4: What does it mean to be an adult? To be responsible?

PERSON 5: Be responsible.

PERSON 6: Independent, responsible and respectful.

LICHTMAN: That last answer – being independent and responsible – is pretty representative of what most people in America think. So says Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, a psychology professor at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. and co-author of “Getting to Thirty.” And he would know.

ARNETT: I’ve been doing research on this question for 20 years now and I’ve found remarkable consistency in how people think about adulthood and how they conceptualize it across ages, across genders, across social class groups, across ethnic groups. The top three, I call them the big three, are accepting responsibility for yourself, making independent decisions, and becoming financially independent. Those are remarkably consistent across many studies by now.

LICHTMAN: You’ve tracked in the last 20 years I think a real change in how people conceive of adulthood. We hear a lot about the millennial generation bucking norms for adulthood, pushing back these traditional markers.

ARNETT: Yeah, 20 years ago, the median marriage age was three or four years earlier than it is now, and it’s just continued to rise. And the same with the median age of entering parenthood. And I was pointing at the time to how higher education had expanded so much, and that was another thing that seemed to make adulthood later. Well, by now, it’s expanded far more, making even more there’s a period of emerging adulthood as I call it in-between adolescence and young adulthood. It’s really a distinct life stage, now, I think.

LICHTMAN: Right. You’ve argued that this time period, it’s basically your 20s, right?

ARNETT: Yeah, basically.

LICHTMAN: Is this new stage of life called emerging adulthood. And I was curious, how does that fit in with biology? When we think about stages of life, are they constructs that we impose on our life or is there some biological underpinning? How do those two things fit together?

ARNETT: That’s a question that some scholars have raised about my theory and about my ideas. They’ve said, “Wait a minute, stages have to be universal. They have to take place for everyone, everywhere. And they also have to be uniform.” Because that’s traditionally how we’ve thought about stages. I mean, Freud’s stages of psychosexual development in childhood and Erikson’s stages of the life span, Piaget’s stages of cognitive development.

They all were proposed to be universal and biologically based. But what I’ve argued is they were all wrong. I mean, we all recognize that they vastly overstated the universality of their theories based on very small local samples. What I’m arguing is stages are useful as long as you don’t claim that they’re universal, because they almost never are. Infancy is about the one life stage I think you can say is really biologically based. You can’t walk and you can’t talk for the first year of life. That’s true everywhere.

But all the other ones, I think, they’re frameworks that we use to understand our development and the development of those around us. And I think once you understand them as social constructions, then emerging adulthood makes sense as a life stage for our time.

LICHTMAN: One of the adulthood themes we keep hearing about are 20-somethings moving back home with their parents–often for financial reasons. And one of Arnett’s most interesting findings is that parents seem to be kind of happy about this.

ARNETT: Yeah. You know, it’s remarkable how happy they are, because we have this sort of cultural narrative if you will in American society that parents can’t wait for their kids to leave. And if the kids do come back in their 20s, then the parents are saying “Oh, no, how could this happen? When are you moving out again?”

It’s funny how common that is as a cultural narrative, and it’s funny especially because it bears almost no relation to reality.

(Sounds of family dining)

LICHTMAN: The Goonan family in Marine Park, Brooklyn seems to make the point. They graciously let me join Sunday night dinner last summer. A weekly family ritual.

B GOONAN: Usually we have several people over. Her brother, my sister.

LICHTMAN: That is Bill Goonan. He’s married to Marion. And their daughter Danielle is here too.

D GOONAN: Sometimes we try to get her to make something other than meat sauce, but it’s rare.

LICHTMAN: Danielle, 29, has a good job. She’s lived alone before, doing a Fullbright in Italy and graduate studies at the London School of Economics. But when she landed a job in New York, she decided to live at home — seemingly very much by choice.

D GOONAN: I like my parents. When I was at school I spoke to my mother every single day. I had friends who didn’t speak to their parents for months on end at college and for me that was the weirdest thing. It’s how you’re raised I guess.

B GOONAN: I think it makes a lot of sense if you get along with your parents.

D GOONAN: We’re an Italian-American family. It’s normal to live at home until you’re married. My mother did it. He did it. So it’s interesting when you go out on a date with a guy, a yuppie, a hipster, all those lovely terms for someone who moved to Brooklyn but wasn’t born and raised here and they give you a face. But in our culture, which is different from your culture, which yes is different from your culture, that’s ok. That’s acceptable. Our families are close.

LICHTMAN: But this isn’t just about feeling connected, it’s also is about saving money–something Danielle became acutely aware of after her dad was seriously injured on the job when she was a kid.

D GOONAN: We were on food stamps. We went from middle class, when you worked for the corporation I think you were upper-middle class, you had the Volvo you had the house. Then all of the sudden she’s driving to other neighborhoods to buy food with food stamps because she’s embarrassed. Because he got hurt. So I’m saving more than 20 percent of my paycheck and I spend another 500/month paying off education loans and I’m able to do that because I live at home.

LICHTMAN: Not that there aren’t negotiations.

D GOONAN: When I moved back it was different in the sense that technically I’m an adult. It’s my parents’ house. So you have to rewrite the rules.

B GOONAN: Believe it or not I’m a little bit of a neat freak. My wife really is not a neat freak. And Danielle is a total disaster. So it goes down the line.

LICHTMAN: How do Bill and Marion like having Danielle around?

M GOONAN: I love having her around. She tends to… (voice) don’t butt in until I’m done. Yesterday I walked down the steps and we have a pool and we’re building a deck and I’m all excited. And I say, “I went to BJs and I bought those disinfectant wipes to wipe off the table.” And she went, “You went to BJs? You know they’re not good.”

D GOONAN: I did not say it like that.

M GOONAN: Yes you did. But this is where we could sit here for 20 minutes and argue.

B GOONAN: To answer your question, outside of what you see now, I love having Danielle around. Listening to the arguments are not the best part.

LICHTMAN: This assessment matches up pretty well with Arnett’s data. In national surveys, Arnett has asked parents whether having their young adult at home is positive, negative or a mix.

ARNETT: Now, I thought most people would say it’s a mix of positive and negative, because really isn’t living with just about anybody a mix of positive and negative? You know, you do have to adjust to somebody else’s patterns no matter who they are.

LICHTMAN: There are compromises no matter what.

ARNETT: Exactly. But remarkably, 61 percent of parents said it was mostly positive. Only six percent said it was mostly negative.

LICHTMAN: So a majority were positive, even though many parents also acknowledged some additional burdens.

ARNETT: They worry more. They are financially impacted by it. But in spite of that, it’s basically a very positive experience. And the emerging adults basically say the same thing. They appreciate their parents’ support. They like their parents.

LICHTMAN: Compare that with how Bill Goonan describes his relationship with his parents.

B GOONAN: I never asked my father for anything. You wouldn’t dare. When you sat at the table he ate first. He took what he wanted and you took what was left and that’s how it was. Our generation we want the kids to have much more than we had. And we’re willing to give up our life for it, which is not good. And unfortunately, most of us don’t realize that until we get up to our 50s and we say you know what we screwed up a little bit. I would have made them work for more things, earn more things and not have that, “I had it so hard, I’m going to make it so easy for them.”

D GOONAN: I worked a lot.

B GOONAN: Even though, there are people that are a lot worse than us, I believe because I’ve seen it. But I would do little things differently.

LICHTMAN: And that brings up a question about Arnett’s theory: does the emerging adulthood stage Arnett is proposing only apply to kids whose parents can support them?

That’s why I wonder what role privilege plays. I guess that’s what I mean with my developed world question. If you have more money, just to put it bluntly, to get education, to explore because you don’t necessarily have to immediately get a job or provide for your family. You have the luxury of thinking about identity in a different way.

ARNETT: Yeah, I think so, too. And no doubt you do. No doubt it makes a lot of difference what kind of opportunities you have for self-exploration in your 20s depending on how much your parents can back you up financially.

But here’s the interesting thing. I mentioned I did this national survey of 18 to 29 year olds, the Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults. And on that survey, I had this question: This is a time of my life for finding out who I really am. Well, about 80 percent of them agreed with that statement, and there was no social class difference.

LICHTMAN: 80 percent of the emerging adults?

ARNETT: Here’s another one, and this is something that has really been striking to me for hole 20 years I’ve been studying this is how optimistic they are.

So, this was one of the survey items on that Clark poll: I am confident that eventually I will get what I want out of life. 89 percent agree with that statement. I am confident that eventually I will get what I want out of life. Wow, nine out of ten are confident, and there’s no social class difference. There’s no ethnic difference. It’s remarkable that even though the 20s are a struggle, almost everybody believes that eventually life is going to smile on them.

LICHTMAN: I wonder how that changes with adulthood onset.

ARNETT: Well I’ll tell you, I now know. I just finished this latest Clark poll, what I’m calling the Clark Poll of Established Adults. It’s 25 to 39 year-olds. Because I’ve always wondered, what happens to those big dreams? Does the bubble get popped? I mean, of course the bubble gets popped. Who does get what they want out of life, right? I mean, by the time you’re in your 50s or 60s, I think everybody will say, “Well, I got some things I wanted out of life but not everything.”

So, I surveyed 25 to 39 year-olds, thinking it’s likely that’s when the bubble would burst. But as it turns out, they’re almost as optimistic in the 30s as they are in the 20s. It’s not quite as high. It’s more like 80 percent to 90 percent. But, they still overwhelmingly agree with that statement: I am confident that eventually I will get what I want out of life.

LICHTMAN: So when does the bubble burst?

ARNETT: I have no idea. I think maybe Americans are just pretty resilient in their optimism, and inclined to see the bright side and to believe that better days are ahead, even if their current lives are not quite what they want them to be.

LICHTMAN: That was Jeffrey Jenson Arnett, Research Professor of Psychology at Clark University and author, with Elizabeth Fishel, of “Getting to 30: A Parent’s Guide to the 20-Something Years.”

OLSHER: You can find more big questions on our website. TRBQ dot org. Catch up with us on Twitter and on Facebook — that’s a good place to ask us your really big question. This podcast was produced by Flora Lichtman. The Really Big Questions is a project of SoundVision productions with funding from the National Science Foundation. I’m Dean Olsher.

These are the final words of Jennifer Michael Hecht’s most recent book: “Choose to stay.”

Hecht argues against suicide as an escape from despair. She offers two reasons. Choosing to stay allows you the chance to be helpful to someone else. And, she says you owe your future self a chance at happiness.

AUDIO: Hecht talks with Dean Olsher about her book, Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It.

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/TRBQ_Podcast16-_Hecht.mp3

VIDEO: Jennifer Michael Hecht reads her poem, “No Hemlock Rock (don’t kill yourself).”

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

[Music plays]

Olsher: I’m Dean Olsher, and you’re listening to The Really Big Questions. It’s the podcast that asks really big questions, and today we’re talking about the decision to end one’s life. I’ll be speaking with the philosopher and poet Jennifer Michael Hecht. Her most recent book is called “Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It.” Our interview took place when Robin Williams was still alive, but the death of Phillip Seymour Hoffman by overdose was still heavy in our hearts.

Hecht clarified she’s not talking about people who have terminal illness. She thinks that shouldn’t even be called suicide, but instead managing how the cancer kills you. She’s talking about suicide brought on by despair. She makes two arguments against taking your life, the first of which she describes as communitarian, and the second, that you owe it to your future self – the person who has overcome the despair – to give that person a chance to live. She first came to her subject not in a scholarly mindset, but as an artist.

Hecht: I lost a friend to suicide, and I was very shocked and miserable from it. We weren’t close anymore. I’d known her for a long time, though, and I kept seeing her. And in a combination of grief and, I’m afraid, empathy in that I, too, had certain kinds of periods of depression that would lead me to similar thoughts, I wrote a poem. Because I write poetry, I can sit down and write things that I don’t have proof of, or even know the end of the sentence. I can feel around and nobody gets hurt, right? It’s a poem. And so I wrote this poem out of grief and an attempt to make it very plain to myself, the argument that I’d come up with.

Olsher: Would you read it for us?

Hecht: Sure. Here it is.

“The No-Hemlock Rock,” by Jennifer Michael Hecht.

Don’t kill yourself. Don’t kill yourself. Don’t. Eat a donut, be a blown nut. That is, if you’re going to kill yourself, stand on a street corner rhyming seizure with Indonesia, and wreck it with racket. Allow medical terms. Rave and fail. Be an absurd living ghost, if necessary, but don’t kill yourself.

Let your friends know that something has passed, or be glad they’ve guessed. But don’t kill yourself. If you stay, but are bat crazy you will batter their hearts in blooming scores of anguish; but kill yourself, and hundreds of other people die.

Poison yourself, it poisons the well; shoot yourself, it cracks the bio-dome. I will give badges to everyone who’s figured this out about suicide, and hence refused it. I am grateful. Stay. Thank you for staying. Please stay. You are my hero for staying. I know about it, and am grateful you stay.

Eat a donut. Rhyme opus with lotus. Rope is bogus, psychosis. Stay. Hocus Pocus. Hocus Pocus. Dare not to kill yourself. I won’t either.

Yeah, I wrote the poem. It was for “Best American Poetry.” And then The Boston Globe contacted me and asked if they could print it. And I got a ton of email, a ton of email from really hurting people, people who were suicidal and many more people who loved someone who was suicidal and lots of people who had already lost somebody. It just moved me so much. I said, “Okay, now I’ve got to find out whether everything I’m saying here is specifically true.”

So, I was saying things about religion having been mostly against suicide. Had I ever researched that? Not in particular. I was saying things about how the secular world and the enlightenment started to reject the church’s power, and that’s when we started to get all, “I have a right to suicide.” So, I just started researching to check my work, and it was in that process that I slowly came to the idea of, “I’m going to write a book about this. I need people to be able to read and know some of these important things.”

There were a couple of things that came out of the research which were profound for me. One is that though I found every wonderful permutation of some of the arguments I was finding, I never found anybody say thank you. Just simply “thank you” to those people who are staying for the community. I think the culture needs that. And so I started saying thank you. Thank you. There are people who are listening right now who are staying alive for other people and who are in pain, and it matters that somebody says thank you.

Olsher: We’ve been tackling this question of what is a good death, and my instinct has been always to think about what is a good death from the point of view of the person who’s dying. But what’s interesting about your book is that you’re writing about the people who are left behind.

Hecht: Yeah, that is one of the big points of what I’m doing in “Stay.” The arguments that I came up with – the first idea I came up with was communitarian, that we need each other, so that even if you feel like a burden, you would be a million times more of a burden if you take your life. And that means that you’re contributing by staying, even if you’re crying and feel useless and pointless and you can’t imagine a time out of it.

Trust your former self. If you can, when you’re happy, write yourself a note. But when you feel terrible, you’re not going to be able to see your way out of it, but you can put in your mind beforehand that suicide can be fatal to others. I really start from fatal, and then I just touch lightly on the pain and misery that people live with. But I really want to say to people if you have children under 18, if you take your life, those children become at the very least twice as likely to kill themselves, which means often decades of agony.

Olsher: Why is that? What is it about suicide that is contagious?

Hecht: Well, I’ll start with saying that almost everything human beings do is contagious. We smoke and stop smoking together; we gain and lose weight together; we decide to have two children; we decide to have three children. These are intense life decisions. We decide to marry or not, or marry someone who makes more or less money than us. I mean, the range of things we do by trend is profound.

And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. Culture and community make meaning, and I trust that meaning to a certain degree. On the other hand, once somebody like you has done it, and that doesn’t always mean somebody you knew or were close to. When someone kills themselves and it’s in the news, the suicide rate for that age and gender and profession tend to go up markedly.

Olsher: I did not know Phillip Seymour Hoffman personally, but I have to say that his suicide through overdose really hit me hard.

Hecht: Yes. Well, I think that one hit us very hard, partially because when people are famous they start to feel like family. But a death is so different than a death by suicide in terms of how it reverberates on us. I agree that when you have 70 bags of heroin in the house and you’ve joked with friends about dying from it, you know, yeah, this is clearly – I think he meant to wake up that day, but it’s suicidal behavior. And yeah, I think one of the worst parts about it for us, for some of us, is that those of us who work very hard do it because we need something. The woman who was happy in the cafeteria may have had a better childhood than the person who is running for president, sometimes, because what is the point of working so hard if you have a real philosophical understanding of what life really is?

And that tends to come down to chasing demons. You’re trying to prove yourself, that you deserve the space you’re standing on. I think Hoffman had it that way, and we all want to believe – people like you and me, who do a lot, we want to believe that when you get paid for it and that famous for it and that praised, praise, praise, praise from intellectuals, from people you don’t have to say “Oh, I . . .” No, from the deepest people. When you have praise, millions of dollars, and that kind of fame and success, and you’re doing good work and have projection to do it for the rest of your life? We want to believe that saves your ass. Sorry, we want to believe that saves you. And the truth is, no. What it does is raise your expectations, but you’re still a human being. You’re going to be in pain, and feel guilty about the pain. You shouldn’t be in pain, right? You did so much. But you’re still a human being. And so you kill the pain with more need. When they get to their goal, they fall apart, I think, to a man.

Olser: This idea of a good death from the point of view of the person who is dying versus the people left behind, they can often be at odds with each other, right? And so you’re privileging the people who are left behind as if their needs take precedence over the person who wants to die more than anything.

Hecht: When I’m talking strictly about despair suicide, I am saying that—by being born into the United States, you adhere to certain rules or you leave. Being born into humanity, one of the strong moral suggestions along with don’t kill anybody else is don’t kill you. And I don’t hear anyone else saying that; I’m getting a lot of pushback on it. People feel very strongly, and they claim their right to death as a gesture of autonomy that’s really a pillar of human independence.

And I am saying, “No, there is interdependence, too.” Teenagers, should they have a right to kill themselves? When your prefrontal cortex is formed at 25, we can at least have the conversation. But we are losing a tremendous number of people between 15 and 24. Tremendous. And that includes the vast majority of the military suicides. But the baby boomers are now suddenly skyrocketing in suicide, women in their 60s, men in their 50s, white, successful. They are killing themselves in record numbers. Right across the culture, we’re seeing a rise. There’s been a definite rise in the United States since 2000.

And the World Health Organization says that in the last 45 years, the suicide rate has gone up worldwide 60 percent. And we’re not sure exactly what that looks like in different places, but we do know that that’s more than war in the vast majority of places, suicide more than war. Everywhere, suicide more than murder. Everywhere. A couple of little exceptions, but in the United States, suicide more than murder every year. We kill ourselves more than we murder.

It’s a barbarism, in a way, that we’re letting this happen. If we can manage to get out of this suicide business, because there have been cultures who seem to have done it much less, what would happen 200 years from now if they looked back and saw that 30-40,000 Americans every year killed themselves either with a gun or rope or pills? It would begin to look like the culture—if we saw that in an ancient culture, we’d call it a sacrifice. And the society that says that everyone has the right to kill themselves is complicit in those thousands of deaths. It is.

[Music plays]

Olsher: We have video of Jennifer Michael Hecht reading her poem “The No-Hemlock Rock” on our website, which is TRBQ.org. And while you’re there, you can hear several other podcasts and an hour-long radio show all asking the question, “What is a good death?” Go find us on Twitter and on Facebook, too. The Really Big Questions is a project of SoundVision Productions with funding from the National Science Foundation. This podcast was produced by Flora Lichtman and me, Dean Olsher.

Maybe it’s a stuffed elephant. Could be a pepper shaker. Or perhaps a very special rock.

Many adults have an object that’s particularly dear to them, but it’s not something that most people openly talk about. Unless you ask them.

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Podcast15_Things.mp3

Share your special thing with us on Facebook

Emily Walsh has always collected trinkets, from coins to keys to board game pieces. When she was a little girl, she carried her special things around in a bag.

When she got to be an adult, she didn’t grow out of this love for special objects. When she traveled, she always carried a little star her sister made for her.

On a backpacking trip to the Himalayas, she started asking the other hikers she met if they were carrying anything special.

She heard many responses: pictures, good luck charms, special rocks.

“It just seemed to be a really widespread phenomenon,” Walsh says. “It is the most interesting to me when you are carrying these things on your back. It really is telling about how important they are to you.”

When Walsh went on to pursue a master’s degree in social work, she read the work of a prominent 20th century British psychiatrist named Donald Winnicott. He said it was natural for kids to get attached to special things, which he called “transitional objects.”

But Winnicott said that adults are supposed to grow out of those things.

Emily Walsh cherishes a pelican figurine that belonged to her grandmother. (Photo: Emily Walsh)

That flew in the face of the stories that Walsh had been hearing for years. She just couldn’t see all of the people she’d been talking to as pathological. So she decided to write a thesis about it.

Walsh asked about 30 adults if she could interview them about a special object in their lives. She defines “special object” as something with “vital meaning.” Something that people don’t want to live without.

In fact, she asked people what it would be like to not have their object.

“People would get silent,” she says. “Or just be like, ‘I don’t want to think about that.’”

The objects people talked about about were varied. They included everything from a table, to a train ball bearing, to a framed copy of the first chapter of the Koran.

The special things that people told Walsh about fit roughly into three categories: charms, mementos and objects with exceptional physical characteristics.

There are many powerful feelings tied to these objects, but they aren’t all positive. Some people told Walsh that their special object can be a burden.

“One of my participants had a bicycle from his father,” she says, “and he was sort of like, ‘Why do I have such a huge heirloom?’ He said as well as being a wonderful reminder of his dad, this is a lot to have to carry around.”

Even people when people consider their object a heavy weight, though, Walsh said they flinch at the idea of getting rid of it.

“If you inherited it, there’s the disrespect to whoever wanted you to have it,” Walsh says. “So maybe you don’t even like this thing, but you can’t give it away because of that relationship.”

Then there are other people, Walsh said, who worry that the thing itself will feel bad if they give it away.

“Someone talked about a stuffed lobster,” Walsh said. “She just felt like, ‘I can’t give this away, because it’ll hurt the thing’s feelings.’”

When Walsh’s interview was over, an odd thing happened at the recording studio. The engineer, Bart Rankin, came out of the sound booth to talk with her.

“I was touched by the interview,” Rankin remembers. “So I walked into the studio and I showed her a special object of my own.”

Bart Rankin showed Mr. Giraffe to Emily Walsh after hearing her talk about adults and their special objects. (Photo: Bart Rankin)

Rankin’s object is a stuffed giraffe that his wife gave him when they first got together.

“It’s part of our relationship, so between the two of us we’ve built up a mythology around Mr. Giraffe,” Rankin says.

Most days Rankin takes Mr. Giraffe with him to work in his bag, but they’ve also seen the world together.

“He’s actually driven on the wrong side of the road in Ireland,” Rankin says. “And you know, most stuffed giraffes have not.”

Until Emily Walsh came into the studio, Rankin hadn’t told anyone outside of the family about Mr. Giraffe. He thought they might think it was silly.

“Of course, I would tend to agree with them that it’s silly,” he says. “As a grown man who’s nearly 50, it’s sort of funny to have a stuffed animal that’s sort of your special friend.”

Rankin thought about it, though, and decided to go public with Mr. Giraffe anyway.

“I suppose if anyone did not want to be my friend, then maybe they’re someone I don’t want to be friends with anyway,” he says, “if they take a stuffed animal that seriously.”

Rankin has always been a collector. He keeps ticket stubs from concerts and programs from events. But before Mr. Giraffe, he hadn’t had one special object since he was a kid.

That’s one place where he and his wife differ. He says she isn’t a collector, but she does hang onto one special thing.

“She has a little, I think at this point, a piece of a blanket that was hers when she was a little kid,” Rankin says. “She hangs onto that and often sleeps with it. “

Many of the people Emily Walsh talked with actually named baby blankets and childhood stuffed toys as their special objects.

One of those people is Walsh’s friend Sophia Slote. Her “Blankie” is the one she was wrapped in as a baby.

Not much remains of Blankie, Sophia Slote’s childhood blanket. (Photo courtesy of Sophia Slote)

“He was originally a rather normal-sized baby blanket,” she says. “Blue on one side, pink on the other.”

Now Blankie has been through a lot, and he looks a little different.

“He’s just a very small—you can hold him easily in both hands—ball of yarn,” she says.

Slote thinks one reason she got so attached to Blankie is that when she was a kid, she split her time between her parents’ homes.

“Blankie was in some ways the most static thing in my life,” she said. “Part of his purpose is to sort of fill the absence that my parents couldn’t really fill at that time.”

Blankie has already seen a lot of wear and tear, and Slote said it’s painful to think about the possibility of wearing him out.

“I will make some big changes so he lasts, I think,” she said. “It’s tricky, though, because in order to get soothing from him, I’m destroying him.”

This next part might be a little hard to believe, but it’s absolutely true. Slote was in the same studio as Emily Walsh, on a different day. A different recording engineer was working, but the exact same thing happened.

At the end of the interview, the engineer came in to tell Slote about her own special object. The engineer’s name was Cara Foster, and her object was—that’s right, a baby blanket.

What remains of Cara Foster’s baby blanket looks a bit more like a shawl. (Photo: Cara Foster)

Foster says the blanket stayed on her bed until she was 23, and she’s just never felt like throwing it away.

“It was always around, until I moved in with my future husband and started sharing a bed and it just kept ending up on the floor,” she says. “I wasn’t cuddling the blanket anymore for comfort; I had somebody else, and it was replaced. But I never pitched it.”

These days, Foster’s blanket is in one of her dresser drawers. It’s in a Ziploc bag with a sweatshirt, a stuffed animal, and a piece of a quilt from her childhood home.

She doesn’t take these things out very often. She just wants to know they’re there.

“I think we all have heirlooms,” says clinical psychologist Susan Pollak. “We all have objects, furniture, jewelry, that have incredible meaning.”

Pollak teaches at Cambridge Health Alliance, part of Harvard Medical School. She said she believes it’s fine, even good, for adults to have special objects. Pollak has heard many stories from adults who have drawn tremendous comfort from beloved objects.

“One of the fascinating things about being a therapist is people tell you things that they wouldn’t tell anyone else because of a sense of shame, or a sense that it’s not quite grown-up to talk about the fact that you’ll bring out your teddy bear or a piece of your blanket when you’re going through hard times,” she said.

Using her grandmother’s rolling pin transports Susan Pollak back to Grandma Tilly’s kitchen. (Photo: Susan Pollak)

Pollak says, though, that she doesn’t think it’s immature at all. In fact, she thinks it’s universal.

“I think we all need some comfort,” Pollak says. “It’s just that we don’t readily share how vulnerable we are.”

Susan Pollak has a special object of her own. It’s a 1930s rolling pin that she inherited years ago from her Grandma Tilly.

“I would use the rolling pin and talk to my daughter and my son about Tilly,” she says. “Then I began to think about how powerful this rolling pin was for me and how in many ways she still seemed to be alive in my kitchen.”

When you start asking, it really does seem like nearly everyone has a special object. That’s certainly what Emily Walsh found. When she was contacting people for her research project, most people told her right away that they had one.

There were only four men who said they didn’t have anything like that.

Then, she called them back a couple of days later.

Walsh said all four responses went something like this: “Oh, yeah, there’s this thing and I can talk for an hour and a half about it because it has that much meaning for me.”

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

Mary Roach wants you to give yourself away. Not yet, though. After you’re dead. She wrote a book called “Stiff,” in which she details what has happened over the years to bodies that were donated—willingly or unwillingly—to science.

“I think that, for many people, does take the edge off it,” Roach says. “You know there is some good coming from something that’s otherwise kind of a bummer.”

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/TRBQPodcast14_MaryRoach.mp3

In “Stiff,” Roach describes unusual and unexpected uses of dead bodies—in great detail. She says for this reason, she was afraid the book would discourage people from whole-body donation.

“Like, ‘Oh my God, you’re going to cut off my arm and use it over here in the test of a car window? And you’re going to take my head to drop it down here to look at skull fractures?’” she says.

But Roach says she saw the opposite result. She received many inquiries from readers who wanted to donate their bodies.

That, she thinks, can make for a “slightly better death.”

Although the idea of doing some good after you’re gone might be cathartic, there are many reasons people hesitate.

Often, Roach says, religion plays a role. Some people feel that they will need their body in tact for the afterlife. Roach says this was the case with one friend.

“On his driver’s license, there was a little tiny line where you could specify what parts,” she says. “He said, ‘Anything below the neck. I don’t want them messing with my eyes. I don’t want to look bad.’”

Mary Roach on the stage at TED in 2009. (Photo by Bill Holsinger-Robinson)

Roach says another reason might be the lack of control. She often hears from people who want to specify what their body will be used for – only for cancer research, for example. But Roach says this is impossible because no one knows what kind of medical research will be going on when they die.

“I always tell people it can’t hurt to make a request,” Roach says, “but you don’t get to control that. And also, P.S., you won’t care because you’re gone.”

That fear of losing control may be a form of denial, but Roach thinks there’s something else to it.

“It’s also wanting to still be there in a way,” she says. “I think it’s impossible to envision a world without us.”

Roach acknowledges that she has struggled with this, too. Her vision of her post-death-life: being a skeleton in an anatomy lab.

“I had this image of myself and my interactions with the students,” she says. “It’s totally irrational, and I think it is an inability to wrap one’s mind around not being here at all, ever, to anybody.”

Aside from the educational skeleton idea, Roach doesn’t have a firm plan for what will happen to her body. She says she got donor forms from Stanford and UCSF in roughly 2004, a year after “Stiff” came out.

“I had those forms sitting around for a long time,” she says. “I don’t know where they went and I never signed them.”

Roach says it’s still her vague intent to donate her body for medical research. But she also has a “romantic notion” of her husband scattering her ashes on a bluff overlooking the ocean.

“I’m playing both sides of the fence,” she says. “I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

If you ever doubt that animals have the capacity to share, look no further than chimpanzees and capuchin monkeys.

Frans de Waal studies primates, and he teaches psychology at Emory University. He says says looking at the way other primates share sheds light on the way humans act.

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/TRBQ_Podcast13_DeWaal.mp3

“Sometimes in human behavior there’s a tendency to say it’s unique,” he says. “People will say we’re the only ones who really share and the only ones who really care about the wellbeing of others.”

Many cooperative animals, like lions and hyenas, have to share to survive.

“What would be the point of me helping you hunt if I never get anything?” de Waal says. “For cooperative behavior, it’s absolutely essential that there’s some sort of sharing of the payoffs at the end, otherwise the behavior would disappear.”

Although a snarling pack of hyenas around a dead zebra may not look friendly, de Waal says, they’re still sharing. They’re not chasing one another away because they need each other to survive.

Then there are other animals, like chimps and bonobos, that share in a more familiar way.

Frans de Waal studies and teaches primate behavior at Emory University. (Photo: Emory Univ.)

“They can even hand things to each other and they have begging gestures,” de Waal says. “Like, you have food and I hold out my hand, an open hand, which is also a universal human begging gesture.”

De Waal says chimpanzees have a sense of fairness. They know if they’ve gotten a raw deal, and they’re unhappy about it. Studies have shown the same thing with human infants and a number of other animals, so it seems the expectation of fairness may be inborn.

De Waal studied this fairness issue first in capuchin monkeys. Two monkeys were given food in exchange for performing a task.

“If you give them the same foods they will keep doing the task forever,” he says.

That changes when you start giving one of the monkeys a better food—grapes, for instance—but continue giving the other one a cucumber.

“Then the one who gets the grapes is perfectly happy,” he says. “But the one who gets cucumber at some point starts refusing and rejecting and objecting and protesting, and even throwing perfectly good food away, because it’s not getting what the other one is getting.”

When de Waal shows audiences video of that experiment, it always gets what he calls a “nervous laugh.”

“(People) are so entrained by society that they are different, that we are better than animals,” he says. “Then they see a monkey show exactly the reaction that they would have under the same circumstances and this makes them a little bit nervous.”

De Waal says there are a couple of forms of fairness. It’s the simplest form that leads capuchin monkeys to protest when they get a slice of cucumber instead of a grape. A more advanced form is based on seeking fair treatment not just for yourself but for others. That is, even if you get the grape, you’re unhappy if your neighbor gets only a slice of cucumber.

Tests show that monkeys, dogs and crows do not possess this sense of fairness, but humans do. And de Waal found that chimps do, too.

“The chimpanzees would refuse the grape until the other one also gets a grape,” de Waal says. “Now, that’s a really advanced form of a sense of fairness. We think it is done to maintain good relationships.”

In Frans de Waal’s book “The Age of Empathy,” he says that humans are inherently altruistic.

But if the purpose of altruism is to maintain good relationships and ultimately benefit ourselves, is it genuine altruism?

De Waal would say yes.

“That’s the sort of discrepancy between evolutionary thinking and psychological thinking,” he says. “In evolutionary terms, every behavior that is typical of our species has to have some payoffs. Otherwise, it never would have evolved.”

De Waal says altruistic acts may have a background of self-interest, but it doesn’t mean that they are selfish at the psychological level.

“Let’s say a child falls and cries and I put an arm around the child,” de Waal says. “That general behavioral tendency has been beneficial for me and my species, but the individual act of me reaching out to the kid and lifting it up and trying to console it can be completely altruistically motivated.”

At the psychological level, De Waal says, he is being a pure altruist by comforting a child. At the evolutionary level, though, the behavior is benefiting his species.

“That’s sometimes confused when people say everything is selfish,” De Waal says. “They’re actually referring to the evolutionary explanations, not necessarily to the psychological ones, because there is genuine altruism in the world.”

De Waal says social Darwinism and the idea that people only have an obligation to themselves is a mistaken view of nature.

“Nature doesn’t operate this way,” he says. “There are many animals who survive by cooperating. … They live in groups because being together is advantageous versus being alone.”

Humans, he says, are a prime example.

“One of the worst punishments you can give a human is solitary confinement,” he says. “That already proves that we are an inherently social species and cooperation is very much a part of our social fabric.”

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

On the altar of a former cathedral in Duluth, Minn., an ensemble of musicians begins to play.

Their notes are piercing and sometimes dissonant. It’s not your typical cathedral music—but then again, these aren’t your typical musicians.

They’re robots.

Musician.mp3">http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/TRBQ_Podcast12_I-Musician.mp3Musician.mp3">Download audio

None of them look like robots, though. They look more like futuristic instruments.

Troy Rogers is their creator, and he introduces them one by one.

First there’s AMI, short for “automatic monochord instrument.” It’s a sheet of clear plastic stood on end with a guitar string stretched across it. Some electromagnetic levers press down on the string to change the pitch. It’s kind of a one-string electric guitar that plays itself.

CARI, a “clarinet-like instrument” on the left, with AMI, a one-string guitar-like robot. (Photo courtesy of EMMI)

AMI represents one kind of musical robot, where the robot and the instrument are the same thing.

The other kind is a mechanical device that plays a traditional instrument, like Rogers’ snare drum. About a dozen robotic arms reach across the top of the drum, poised to tap or pound the drumhead.

Rogers built most of these robots with two other composers. Troy, Steven Kemper and Scott Barton started making robots together while they were in grad school, back in 2007. Their collective is called Expressive Machines Musical Instruments, or EMMI.

“Now we live in different places and have joint custody of the robots,” Rogers says.

He introduces a clarinet-like robot next. This one’s a clear plastic tube that stands about 3 feet high. It has valves along its length, and Rogers’ computer operates those to change the pitch.

Rogers demonstrates the robots’ capabilities by having them play a piece based on Bulgarian folk music.

The composition lives on Troy’s laptop as computer code. A wire runs to each robot, and the robot performs what the composer has written.

Although the music is written on a computer and triggered by a computer, it’s not “computer music.”

The sound is created by real, physical instruments.

Those real instruments are initially what got Rogers started in music. He says he grew up playing guitar in bands.

“I was grounded for some youthful transgression and I read Frank Zappa’s autobiography,” he says. “He talked about being a composer, and I sort of glommed onto that.”

The term “composer” was new to Rogers, since he didn’t grow up with classical music. He liked Zappa’s take on it.

Rogers’ summary: “You can do whatever you want, and as long as you put a frame around it and call it music, then that’s what it is.”

Troy Rogers queues up his ensemble to play a piece based on Bulgarian folk music. MADI, a snare-drum robot, is in the foreground.

Once you accept that broad definition of music, Rogers says it’s natural to embrace music made by machines. He says mechanical instruments got their start long before computers.

“From carillons in the low countries of Europe in the 13th century, to orchestrions in the 19th century and player pianos,” Rogers says, “electronic music is just a little side stream in that current of music technology.”

Rogers is finishing his Ph.D. in Music Composition and Computer Technology at the University of Virginia. He didn’t start out interested in building robots. He says he wasn’t one of those kids who likes to build stuff.

“No, I broke stuff, but I didn’t really build anything,” he says with a laugh. “I was more into destruction. I was into explosive devices.”

He lived through that phase, thankfully, and eventually found himself in graduate school.

A couple of years in, he wrote some music for a digital player piano. But he was frustrated by the instrument’s limitations. So he started taking electronic devices apart and figuring out how they worked.

Rogers’ first baby step toward building robots was to make an LED blink.

“Once you make an LED blink, it’s a short step to say, ‘Well, let’s make a motor spin or a solenoid trigger,’” he says. “Suddenly I found myself with a pencil and a paperclip and a rubber band and a steel bowl with a balloon stretched over it, making a little mechanical drummer. And from there, that’s how everything kind of started.”

Troy Rogers’ robot ensemble performs on the altar at the Sacred Heart Music Center in Duluth.

Rogers kept learning from the Internet. Then he found other people who wanted to build musical robots, and they learned together. That’s when they formed EMMI.

Troy says he’s a musician who just happens to have taught himself a lot of computer programming and engineering, but he’s not an engineer.

“There’s engineering that goes into building these things, but I don’t think like an engineer,” he says. “We’re not trying to build something that solves a particular specified problem in the most efficient way.”

In fact, sometimes Rogers and his friends do the opposite.

“Sometimes the inefficient solution is the most musically interesting,” he says.

Rogers still writes occasional pieces for voice or solo piano, but he says he’s drawn to robots because they can do things that humans simply can’t.

“It might be complex rhythmic relationships and structures, polyrhythms that are outside the realm of what humans can perform,” he says. “Rather than just a 3 against 2 feel, it might be an 82 against 85 against 89 notes in a given time period.”

Robots can play faster than humans, too.

“Some of those trills or tremolos are happening at 40 times or 50 times a second,” Rogers says as one of his robots demonstrates.

That precision is great, but Rogers says it’s only part of why he likes to work with robots.

“On the other hand, sometimes you want to be surprised,” he says. “So you find the voice of the instrument.”

Rogers says experimenting with robots is no different from experimenting with acoustic instruments.

“Whether it’s multiphonics on a wind instrument or whether it’s a robotic instrument trilling at a rate that’s just below the absolute top threshold, you get into these sounds that you can’t produce another way,” he says. “And sometimes that’s what we’re looking for as musicians.”

Still, Rogers says robots have their own set of limitations. Or maybe it makes more sense to say that trained human musicians bring things to music that robots don’t. Expression, for instance, and vibrato.

“One dot on a piece of paper in a certain spot and you get all of that with a human performer,” he says. “It takes a lot more information and a lot more specification to get something as interesting out of a computer or a robot. A human performer just does it out of the box.”

Sometimes Rogers emulates a more human sound with a robot.

Enter the fourth member of Rogers’ quartet.

This one roughly simulates the human voice. Rogers built it with a friend in Belgium. He spent a year there on a Fulbright Scholarship working with what’s billed as the “world’s largest robot orchestra.”

Two Helmholtz resonators produce the sound in Rogers’ vocal robot. (Photo courtesy of Troy Rogers)

Rogers says this robot generates sound from two “tunable Helmholtz resonators.”

“If you think of a beer bottle, if there’s less liquid, you have a lower pitch,” he explains. “And if there’s more liquid, you have a higher pitch. They’re a lot like that.”

Rogers can change the vowel sound the robot makes, from “ah” to “oh” to “ee” to “oo.”

Once the full robot quartet is plugged in and ready to go, Rogers queues up a piece based on Ugandan folk music.

His instruments begin to play—just as they do every time he asks them to.

“Where I used to be almost exclusively a composer, now I’ve become an instrument builder as well,” Rogers says. “Robots end up taking a lot of my time. They’re time-consuming devices.”

The robots might require a lot time and energy, but on the plus side, Troy Rogers has a house orchestra that’s always ready to play.

And they hardly eat anything.

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

The human instinct to tell stories is strong. So strong, in fact, that sometimes people see stories when they’re not there.

Simmel.mp3">http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/TRBQ_Podcast11_Stories_Heider-Simmel.mp3

Simmel.mp3">Download audio

In the 1940s, two researchers set out to demonstrate the proclivity of humans to see stories, even in random events.

Fritz Heider and Mary-Ann Simmel created a short animated film in which a small triangle, a large triangle and a circle all bounced around a box on a two-dimensional plane.

There was no plot. There was no drama.

Yet viewers saw a story unfold in the random movements of the shapes. And 70 years later, the video still activates that storytelling instinct in people. See for yourself.

The students of M.S. 88, a middle school classroom in Brooklyn, are no exception.

When English teacher Keith Christiansen showed his students the Heider-Simmel movie, he heard everything from “the big triangle is beating up the small triangle” to “you could say that the big triangle was desperate for a friend.”

Brooklyn middle school teacher Keith Christiansen asked his students what stories they saw in the Heider-Simmel movie. (Photo: Flora Lichtman)

Finally, one student summed up what they were all experiencing.

“The video’s a blank canvas and then our mind and experiences are the paint,” he said. “Then we just apply that to the video, and then we get what we get.”

Humans may be able to paint that blank canvas easily enough, but it turns out the Heider-Simmel video is one of the toughest nuts to crack in the field of artificial intelligence.

Andrew Gordon, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California, is trying to program computers to do what those eighth graders in Brooklyn did.

“I’m trying to build a computer that can … interpret what’s going on, anthropomorphize the triangles and circles in those movies, and come up with a real narrative that is insightful or that is human,” he said.

Gordon said he’s fascinated by how easy the Heider-Simmel exercise is for people.

“They’re so good at watching trajectories of triangles moving around the screen and coming up with these deep explanations of their emotional state, of their plans and goals and their fears and their personal relationships with each other,” he said. “The truth is, it’s super, super hard for computers.”

The problem, Gordon said, is that common-sense knowledge about human psychology that comes with being human.

If someone is robbed, they will be angry. If someone is in love, they may do silly things.

“Who’s going to tell that to a computer?” he said. “You have to write down all those rules.”

Gordon said computers don’t have many compelling things to say quite yet.

“The lives of computers right now are not very interesting,” he said. “There’s a lot of reading and writing from hard drives. Not the stuff of great Hollywood storytelling.”

That doesn’t matter so much to Gordon. The end result of his work is not entertainment.

“There are some times we want to hear stories from computers because we can get them to watch stuff that would be too expensive to have humans watch,” he said.

Navy Specialist 2nd Class Dennis Rivera monitors a radar console in the Persian Gulf during the summer of 2013. (Photo: Billy Ho, U.S. Navy)

Gordon’s project is funded by the Navy.

“Now, why would the Navy care about triangles moving around screens?” Gordon said. “If you look at a Navy radar, it’s populated with a lot of triangles moving around.”

Gordon’s computers could eventually be watching the triangles on that radar to root out patterns and intentionality.

“I’m very happy to have my computers stare at triangles moving around screens … and be able to craft a narrative or a message,” Gordon said, “so that it could be understandable to a 19-year-old sailor on the deck of one of these ships.”

Andrew Gordon created an online game that allows you to animate your own Heider-Simmel-like movie, and to narrate other people’s creations. Gordon uses the data to refine his algorithms. It’s free, and it’s called Heider-Simmel Interactive Theater.

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

Storytelling is an integral part of human culture. It teaches, enlightens and connects.

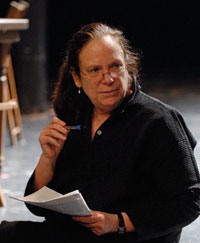

But according to author and playwright Anne Bogart, it can also be dangerous.

http://trbq.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/TRBQ_Podcast10_Stories_Bogart1.mp3

Bogart just released a book called “What’s the Story: Essays about Art, Theater and Storytelling.” She’s also the artistic director of SITI Company, a New York-based theater company.

Bogart believes stories have the potential to distract and deceive—yet she devotes her life to telling them.

Part of her aim, she says, is to tell stories in a different way.

“I think that there are two ways you can tell a story,” she says.

One of them is the Steven Spielberg way.

“I think the intention is for every person watching to feel the same thing,” Bogart says.

Bogart is not impressed by a mere tugging of the heartstrings.

“I’m not a fan of Spielberg,” she says.

She says it’s easy to make her cry.

“I cry at advertisements,” she says “You have a little boy and a dog who have been separated for a month and they run across a field, I burst into tears. But that’s actually cheap.”

Anne Bogart is the co-founder and co-artistic director of SITI Company in New York. (Photo: Michael Brosilow)

The other way to tell a story, Bogart says, is to create moments in which each person in the audience feels something different.

“Much, much trickier,” she says. “Requires more responsibility.”

Bogart calls the first method of storytelling “fascistic art.” Her definition is “a story that has everybody feeling the same thing.”

“I say fascistic and I mean it literally,” she says. “The role of fascist art was to make one feel small and the same. And the role of humanist art, I would just make up a name, is for everyone to feel that they take up a lot of space and that they have an imaginative and associative part to play.”

This, according to Bogart, is the way to tell stories that are empowering rather than dangerous.

“Participation is key to telling a story that does not simply distract, but actually helps live better,” she says.

To sum up her artistic mission, Bogart quotes the pianist Alfred Brendel.

“He said that when he gets in concert to the end of a sonata, just before the last chord, he lifts his hands in concert and silently asks the audience how long he can wait until he plays the final chord,” Bogart says.

That relationship is the key that Bogart says will keep her in theater forever.

“The theater is mostly mimetic, meaning it is embodied,” she says. “If you’re watching a play, your mirror neurons are actually going wild and doing the same thing as the actors are doing, and your action as an audience is to restrain yourself from doing.”

Bogart says this is what sets the theater apart from other art forms, such as film. In theater, she says, the audience is acting with the actors.

“That’s a very active relationship that story can provoke,” she says. “So I think story is a method to create more aliveness rather than less.”

This aliveness is in direct opposition with what Bogart calls the addiction of our time: the “ping” addiction to electronic devices.

“A story demands more from a human being,” she says. “Stories are beautiful little mini-worlds that do require sustained attention and empathy, which is something we seem to be suffering in its lack.”

Rather than being a distraction, Bogart says storytelling may present a solution.

“Perhaps it is an antidote,” she says.

There is a dark side to storytelling, though.

“Stories are super dangerous, and I think it’s why most of my life I resisted them,” Bogart says. “And yet … stories are a tool. So the question is how can you be responsible with stories, and can you find room for discourse inside of stories?”

Bogart acknowledges all of the dangers.

She uses words like “powerful” and “seductive,” saying stories have the potential to become “fascistic” and to be used as propaganda.

“And yet in the theater, in my business, we are in the business of transporting stories through time,” she says.

Bogart says stories that deal with universal human struggles are the ones that live on.

“The great Greek plays, for example, still exist because we’re still hubristic and the stories are about us dealing with hubris,” she says. “So yes, stories are dangerous but also stories are necessary.”

MORE AUDIO from TRBQ:

Subscribe the to the TRBQ podcast on iTunes.

Listen to the TRBQ podcast on Stitcher.

Follow TRBQ on SoundCloud.

This podcast could use a review! Have anything to say about it? Share your thoughts using the button below.

Submit Review